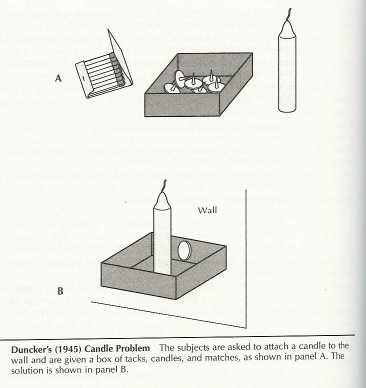

Functional fixedness is defined on Wikipedia as "a cognitive bias that limits a person to using an object only in the way it is traditionally used." Karl Duncker illustrated this concept through his candle problem experiment. In this experiment, participants were given a candle, a box of tacks, and matches and asked how they could hang the lit candle on the wall without dripping wax on the table below. The simple solution is to put the candle inside the box and tack it to the wall. The wax would then drip into the box instead of on the table. See the illustration below.

However, very few respondents saw this obvious solution. The reason is functional fixedness. Participants could not see beyond the function of the box as a receptacle to hold the tacks and therefore did not consider the box as a tool to solve their problem. Interestingly, five year olds when posed with this same experiment had no problem solving it. People aged seven and up started to see the box only for its originally intended purpose as a box for tacks which could not be used in solving the problem. This cognitive bias then is not a limitation we are born with. It is something we learn with experience.

Functional fixedness is not just a challenge when solving engineering problems but can be viewed much more broadly as a bias we face in every aspect of life when trying to "think out of the box".

In addressing challenges, we are limited by what we know. We often cannot see beyond our worldview to consider possibilities that might be directly in front of us but are not a part of our everyday experience. I view education as the process of helping learners discover what they don't know but might want to learn more about. This is what former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld called the unknown unknowns, the aspects of our world that are so hidden from us that we don't even know that we don't know about them.

In responding to Tzvi Hametz's query about Jewish sources for functional fixedness, I immediately turned to the biblical account of the Exodus in this past week's Torah portion.

After the Israelites were freed from Egypt, Pharaoh had second thoughts, sending more than six hundred chariots and officers to overtake the Hebrew multitude. When the Israelites saw the army of the Egyptians bearing down on them, they became frightened and cried out to Moses.

"Was it for want of graves in Egypt that you brought us to die in the wilderness? What have you done to us, taking us out of Egypt? Is this not the very thing we told you in Egypt, saying, ‘Let us be, and we will serve the Egyptians, for it is better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the wilderness’?” - Exodus 14:11-12

The medieval commentator Ibn Ezra poses a fascinating question. The Children of Israel at this point consisted of more than six hundred thousand men of military age plus women and children. They could have easily turned to fight the Egyptians who they greatly outnumbered by more than one thousand to one. Why didn't they fight?

The Ibn Ezra answers with a deep psychological insight into the mental state of the recently freed Israelite people which influences their forty year sojourn in the desert.

Stand and see the deliverance of the Lord: Since you will not make war on Egypt. Rather you will see the deliverance of the Lord that He will do for you today. One may wonder how [such] a large camp of six hundred thousand men would be afraid of those pursing after them. And why did they not fight for their lives and for their children? The answer is that the Egyptians were the Israelites' masters. And [so] this generation that went out of Egypt learned from its youth to tolerate the yoke of Egypt and had a lowly image. And [so] how could they now battle with their masters? And Israel was [also] indolent and not trained in warfare. Do you not see that Amalek came with [only] a small group and were it not for the prayer of Moses, they would have overpowered Israel. And the only God, 'who does great things' and 'for whom all plots are contemplated,' caused that all the males of the people that went out of Egypt would die. As there was no strength in them to fight against the Canaanites, until a new generation, after the generation of the desert, arose. And they did not see exile and they had a [confident] spirit, as I mentioned in the words about Moses in the Parsha of Eleh Shemot (Ibn Ezra on Exodus 2:3). -Ibn Ezra on Exodus 14:13

Having lived their entire lives as slaves to their Egyptian masters, the Israelites could not see beyond this. The Egyptians were forever their masters who controlled them. To turn and fight against their masters, even when they greatly outnumbered them, would have been unthinkable for the Hebrew former slaves. Only Moses who was raised as a prince of Egypt rather than a slave was free from this cognitive bias.

This slave mentality was a theme of the Israelite sojourn in the desert. They were completely passive and helpless in the face of any problem, complaining to Moses at every turn about their lack of food, water, or other basic needs. Their forty year stay in the desert was a necessity in order to raise a new generation of free people who would be able to conquer and settle the land of Canaan.

When contemplating the tremendous insight of this Ibn Ezra, I wonder in what areas I am a slave to my surroundings. Where am I fixated to a specific world-view, the way I was raised, the education I received, the way things are, which prevents me from seeing beyond?

As an educator this question is particularly poignant and as a Jewish educator even moreso.

On the one hand, I wish to lead my students to become a link in the chain of our mesorah, our Jewish tradition, dating back thousands of years so that they too can be an active participant in what Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik affectionately called the conversation of generations.

On the other hand, I wish for my students to be free rather than fixated. I want them to think out of the box about the known unknown and strive to discover the unknown unknowns as well. This is the challenge of a 21st century Jewish educator. We seek to help free ourselves and our students from the shackles that cause us to become cognitively stuck, fixated on what we see before us in our world so we can become truly free men and women in the promised land.

No comments:

Post a Comment